The Radical, 600-Year Evolution of Tarot Card Art

What would Antoine Court de Gébelin think of the Happy Squirrel?

De Gébelin was a Protestant minister born in the 18th century. He authored the multi-volume tome Le Monde primitif, which insisted that the tarot deck contained secrets of the ancient Egyptians, whose priests had distilled their occult wisdom into the cards’ illustrations, imbuing them with great mystical power. Before that point, tarot was primarily a card game—meant for fun, not prophecy.

It was a bold and somewhat absurd assertion, given that de Gébelin could not read Egyptian hieroglyphics (no one could at the time, since they weren’t deciphered until the 19th century). Despite a total lack of historical evidence to back his claim, the theory stuck: Tarot decks, once a novelty, became popular tools for divination after the publication of de Gébelin’s book.

Which brings us back to the Happy Squirrel, a relatively recent addition to the tarot’s Major Arcana, and one whose provenance is less hazy: it originated on season six of The Simpsons. Lisa visits a fortune teller who is unconcerned when Lisa picks Death, but gasps in horror when the next card she draws is the Happy Squirrel. (When Lisa asks if the fuzzy rodent is a bad sign, the fortune teller demurs, saying that “the cards are vague and mysterious.”) Although it began as a cartoon joke, the Happy Squirrel card has made its way into over a dozen commercially available tarot decks.

So what would de Gébelin’s reaction be? The answer depends on whether tarot is a collection of timeless, mystical wisdom—or a flexible framework that has endured by changing with the times. Although tarot imagery employs supposedly universal archetypes, new decks are constantly being invented, and old decks altered. The art of tarot cards can never fully transcend its milieu. Which begs a second question: How do the cards’ art and design relate to the social changes, technological advances, and aesthetic sensibilities of their particular eras?

A Wealthy Family’s Trick-Taking Game

-

Bembo Bonifacio, Female Knight (Swords), 1428-1447. Visconti Tarot from the Cary Collection of Playing Cards. Courtesy of the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale University. -

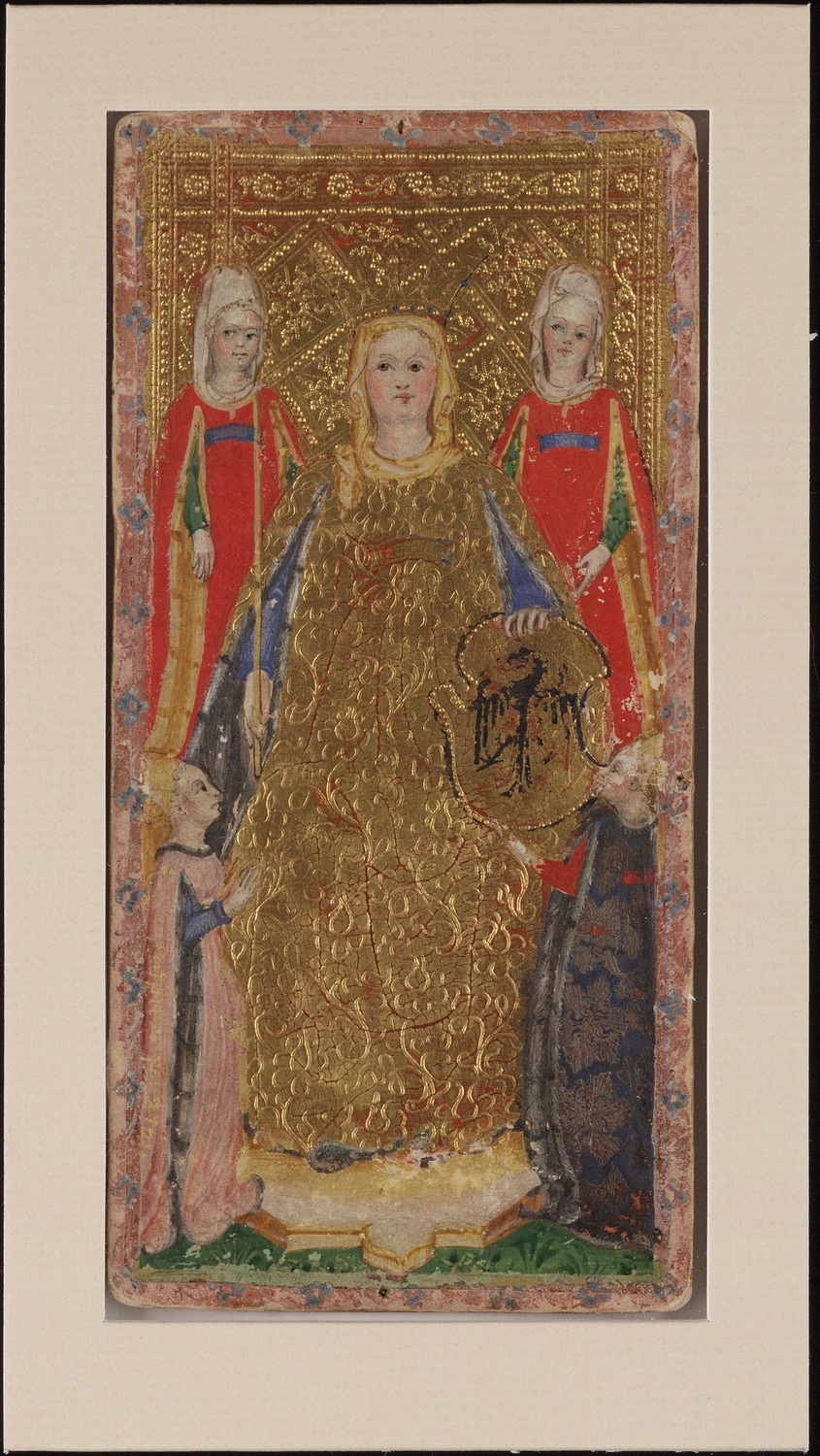

Bembo Bonifacio, Empress of Swords, 1428-1447. Visconti Tarot from the Cary Collection of Playing Cards. Courtesy of the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale University. -

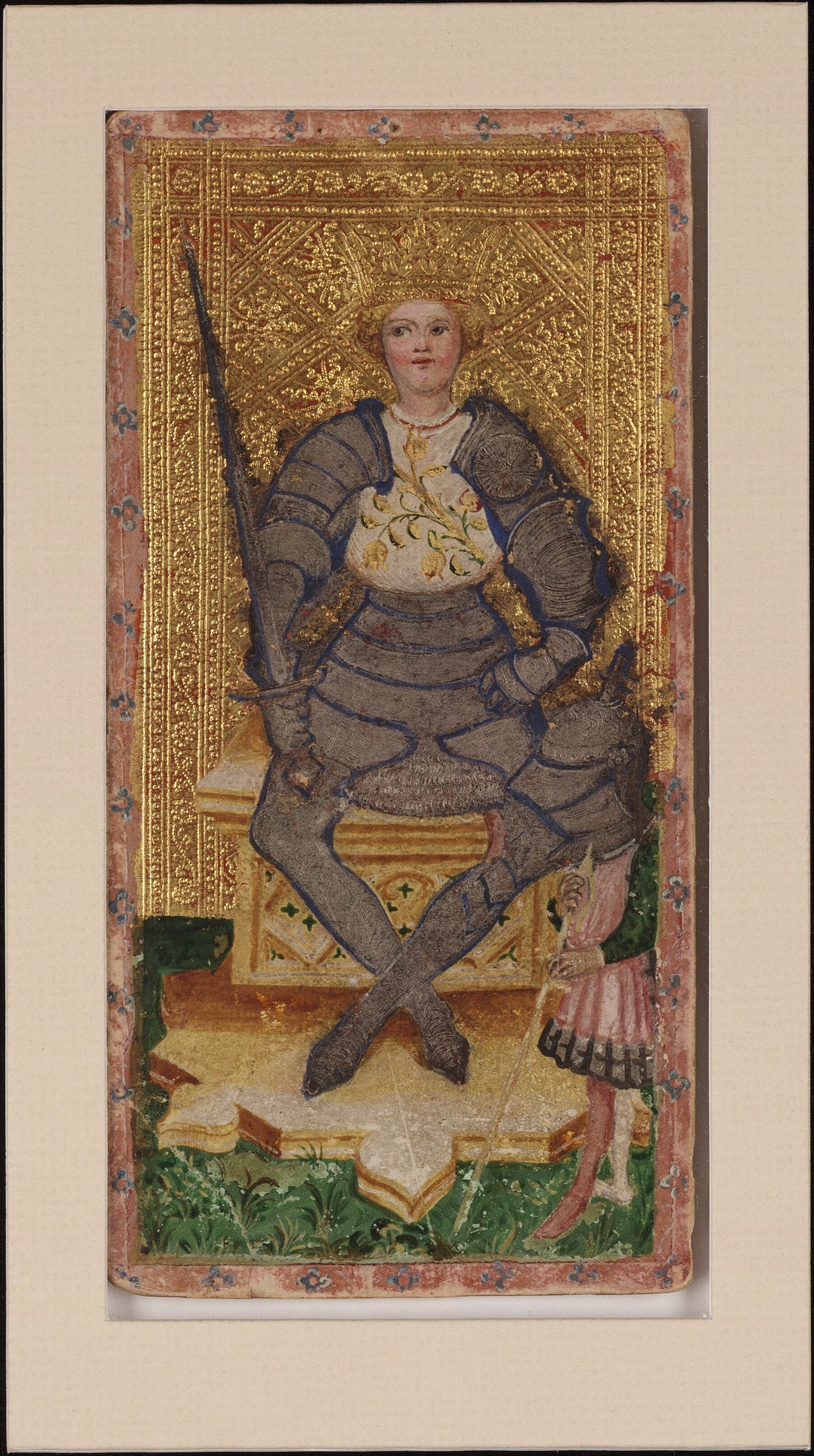

Bembo Bonifacio, The King of Swords, 1428-1447. Visconti Tarot from the Cary Collection of Playing Cards. Courtesy of the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale University.

Despite their aura of mystery, medieval tarot cards were not used for divination, and were probably not created by ancient Egyptian magicians. The earliest surviving tarot decks—now preserved in various museum collections—are Italian, and were commissioned by wealthy patrons, the same way one might have hired an artist to paint a portrait or illuminated prayerbook.

The Visconti-Sforza Tarot is a collection of decks, none complete, commissioned by the Visconti and Sforza families from the workshop of Milanese court painter Bonifacio Bembo. Cards such as Death, who rides a horse and swings a giant scythe like a player in the world’s most high-stakes polo match, will seem familiar to contemporary enthusiasts. So will the Pope, who sits on a golden throne; and the Lovers, who hold hands beneath a string of heraldic flags. Rather than looking to these cards for mystic guidance, the Visconti and Sforza families would have used them to play a trick-taking card game similar to modern-day Bridge. (Although it’s unlikely—given the good condition of the decks—that they were ever handled with much frequency).

The cards each have intricately tooled gold backgrounds that glow like the luxury items that they were. Bembo is believed to have included portraits of the families in many of the cards, as well as adding the Visconti family motto here and there for good measure. Akin to the work of Fra Angelico and other early-Renaissance artists, the cards are opulent but pictorially flat, although the bodies appear in naturalistic perspective and their clothing billows around them, suggesting volume and form.

The 18th-Century Conver Classic

-

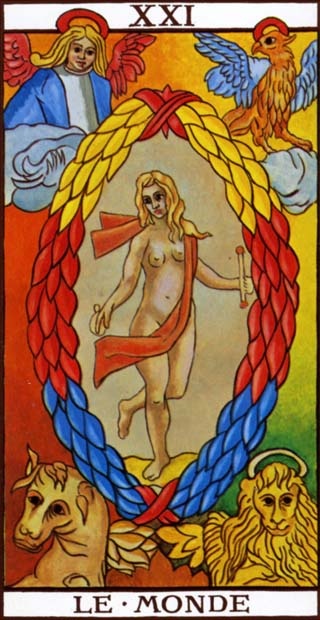

Nicolas Conver, Tarot card from Tarot de Marseille, ca. 1760. Via Wikimedia Commons. -

Nicolas Conver, Queen of Clubs. Tarot card from Tarot de Marseille, ca. 1760. Via Wikimedia Commons. -

Nicolas Conver, Tarot card from Tarot de Marseille, ca. 1760. Via Wikimedia Commons.

Produced in 1760, French engraver Nicolas Conver’s deck of delicate woodcuts, the Tarot de Marseille, is the template on which many contemporary decks are based. Like the Visconti-Sforza Tarot, the deck’s design likely originated in 15th-century Italy before traveling north to France. It’s a favorite of many tarot enthusiasts, most notably the cult film director Alejandro Jodorowsky, who designed his own deck based on the style. While the Conver deck wasn’t the first to be called the Tarot de Marseille, it’s highly prized by collectors for its delicate color palette of sky blues and minty greens. The graphic black outlines and blunt shading of the prints give the cards a simple and rough-hewn appearance, which adds to the ambience of ancient wisdom. The popularity of the tarot grew due to advances in printing technology and via the writings of 19th-century French occultists such as Éliphas Lévi and Etteilla, which popularized the use of tarot as a method of fortune-telling and assigned additional divinatory meaning to the cards.

The New Mystics

-

Pamela Colman Smith, The Empress, c. 1937. Courtesy of the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale University. -

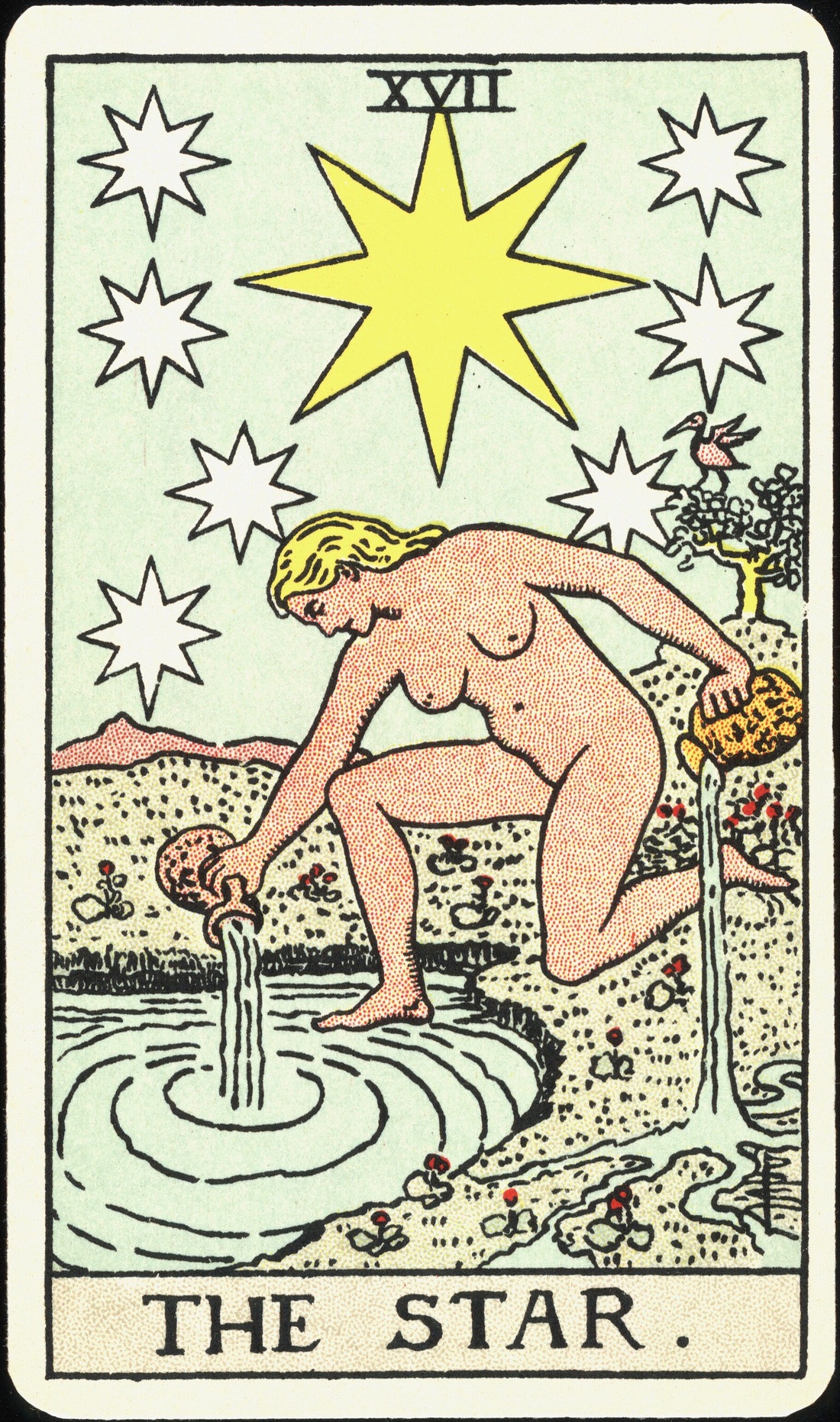

Pamela Colman Smith, The Star, c. 1937. Courtesy of the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale University. -

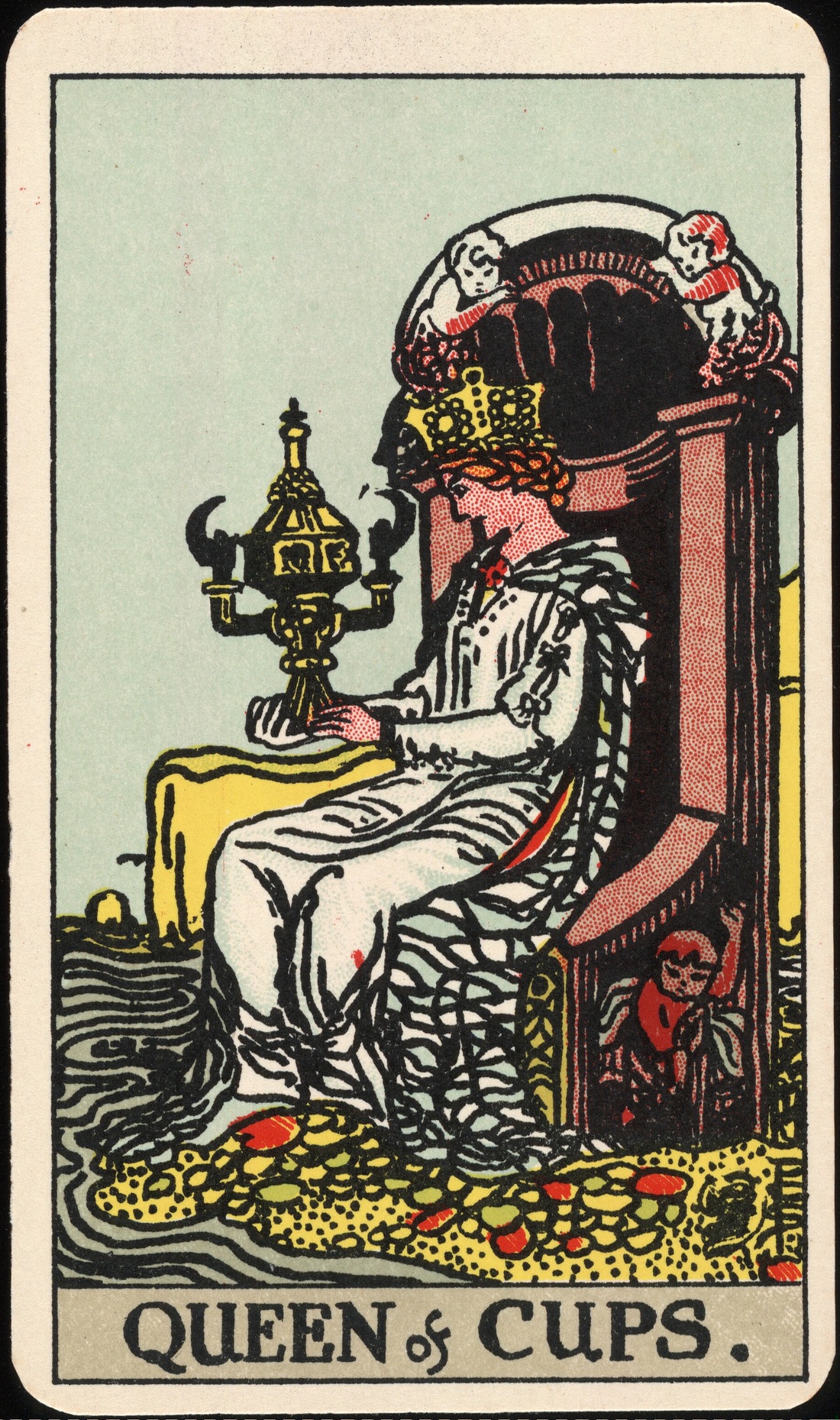

Pamela Colman Smith, Queen of Cups, c. 1937. Courtesy of the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale University.

The Rider-Waite Smith deck, which debuted in 1909, remains the most recognizable and popular today. Designed by artist Pamela Colman Smith under the direction of the mystic A.E. Waite, it was the first to be mass-produced in English, and was intended for divination rather than gameplay. Smith and Waite were both active members of the Order of the Golden Dawn, a secretive organization devoted to the exploration of the paranormal and occult (allegedly Bram Stoker, Aleister Crowley, and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle were also members).

In addition to Smith’s occult bonafides, she was also an accomplished artist, championed by Alfred Stieglitz, who collected her work and showed it at his gallery. Smith created fully-realized illustrations of all 78 cards that made the deck a treasure-trove for cartomancers, who now had a much richer store of images to work with. (Previously, only the 22 Major Arcana cards such as the Fool, the Magician, and the Lovers had been elaborately illustrated—traditionally, the Minor Arcana cards, which are roughly analogous to the suits in a deck of modern playing cards, were not.) The Major Arcana were based on the Tarot de Marseille drawings, but rendered in an illustrative Art Nouveau style rich with patterns. Even the Fool looks debonaire; he carelessly approaches the cliff, a feather in his cap and a blooming rose in his elegant fingers, wearing a floral tunic that looks straight out of William Morris’s workshop.

An Occultist’s Pure Geometry

-

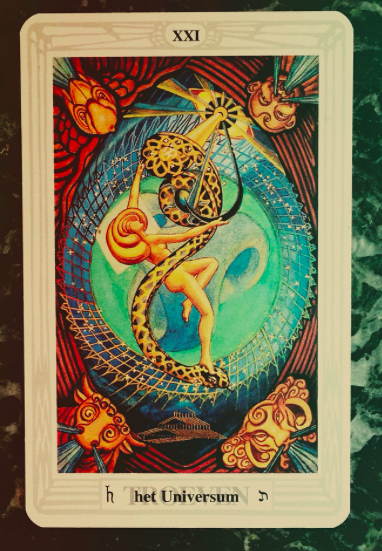

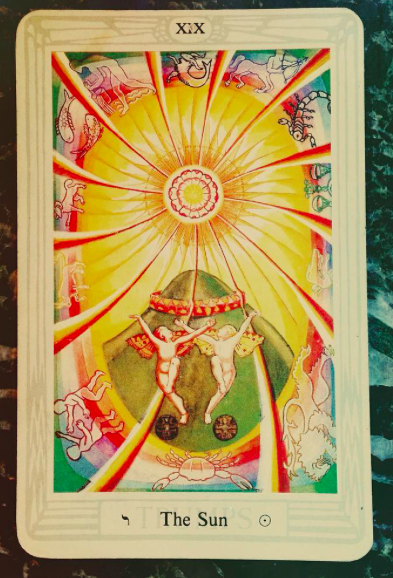

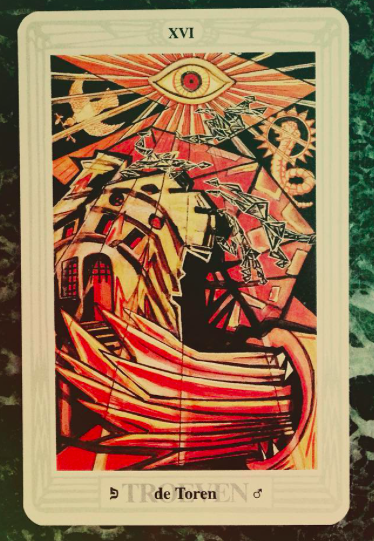

Frida Harris, tarot card from The Thoth deck. Photo by @cugeltje, via Instagram. -

Frida Harris, tarot card from The Thoth deck. Photo by @cugeltje, via Instagram. -

Frida Harris, tarot card from The Thoth deck. Photo by @cugeltje, via Instagram.

The Thoth deck, named for the Ibis-faced Egyptian god more commonly known as Horus, was painted by the artist Frieda Harris based on direction from the infamous occultist-about-town Aleister Crowley. Completed in the early 1940s, but not widely available until 1969, it features Art Decoborders resembling the pattern of a butterfly wing.

The deck is an aesthetic departure from the Rider-Waite’s homey Arts and Crafts aesthetic. Shaped by Harris’s interest in pure geometry, the cards are reminiscent of the work of Swedish painter Hilma af Klint (a visionary artist who shared Harris’s interest in spiritualism and the writings of Austrian philosopher Rudolf Steiner, both popular subjects of study among the middle and upper classes in the early 20th century). Harris’s shaded orbs and compass-inscribed curves that fill the background of each card bear more than a passing resemblance to Klint’s highly-saturated geometries. Klint, considered by some to be Europe’s first abstract painter, believed that her luminous compositions were the created under the influence of spirits. (The same could easily be said of Harris because she was taking direction from Crowley, who was believed to be a medium, able to channel ancient and magical forces.)

It’s no coincidence that Klint’s paintings and Harris’s Thoth illustrations were shown in the same pavilion at the 2013 Venice Biennale, which was intended to amplify voices that had previously been excluded and “cover 100 years of dreams and visions,” according to curator Massimiliano Gioni.

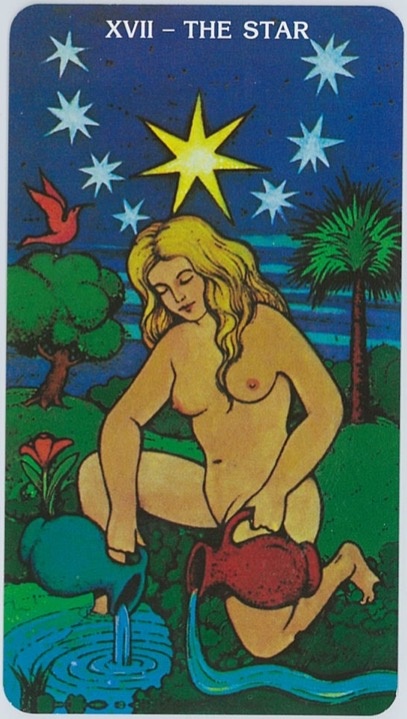

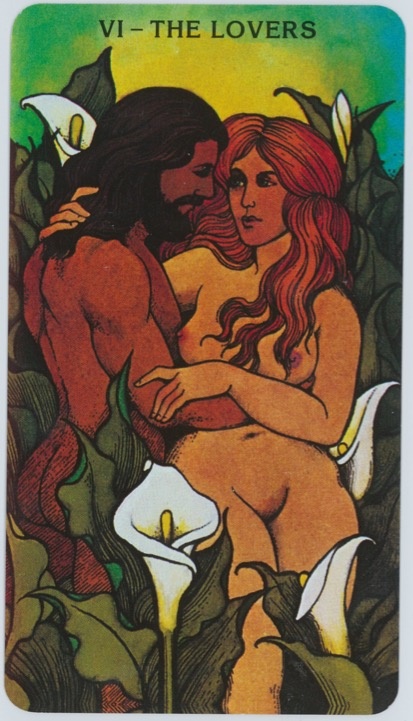

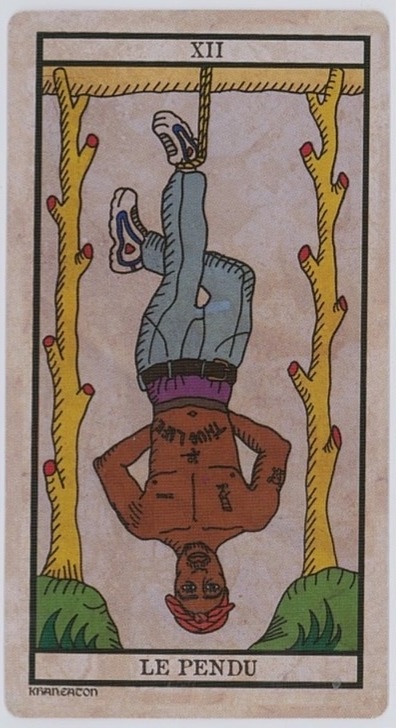

Sex & Self-Help, ’70s Style

-

Bill Greer and Lloyd Morgan, card from Morgan-Greer Tarot, 1979. -

Bill Greer and Lloyd Morgan, card from Morgan-Greer Tarot, 1979. -

Bill Greer and Lloyd Morgan, card from Morgan-Greer Tarot, 1979.

Created by the artist Bill Greer under the direction of Lloyd Morgan, the Morgan-Greer deck is, like the 1970s themselves, both opulent and optimistic. The Magician sports a mustache that would make Tom Selleck blush, and the naked and embracing Lovers would fit right in with the hirsute and curvaceous illustrations in the original 1972 edition of The Joy of Sex.

The ‘70s enthusiasm for all things New Age created a renewed interest in tarot as a tool for self-discovery, and the Morgan Greer deck was there to greet it. The cards’ colors are lush and the lines are fluid. Greer chose to crop his figures tightly and removed the borders, allowing the illustrations to extend to the edges. The effect is fresh and personal. Formally, the Morgan-Greer illustrations have more in common with Jefferson Starship’s Spitfire (1976) album cover than with contemporary painting of the same period—the pendulum had swung away from figuration and would take a few years longer to swing back—but it’s possible to find a resonance between this deck’s art and a work like Judy Chicago’s Dinner Party (1979), with its powerful goddess and blooming flowers. Greer’s strong women and frank sexuality make the deck very much of its time.

Minimalism & Identity in the Present Day

-

King Khan, card from the Black Power Tarot. -

King Khan, card from the Black Power Tarot. -

King Khan, card from the Black Power Tarot.

read more of the original article here https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-radical-600-year-evolution-tarot-card-art

Get a Tarot card reading with me http://www.taratarot.com

Reblogged this on Tarot Daily.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Lost Dudeist Astrology.

LikeLike

“The Oldest book of Wisdom, Tarot, is a symbolic book of initiation which contains the greatest secrets in symbolic form.” Franz Bardon.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes i feel that the tarot is ancient and was merely printed in the 13th -15th century for the 1st time

LikeLiked by 1 person